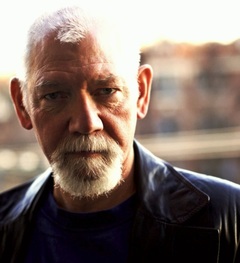

Robert Miltner Q & A with Eastern Iowa Review

Chila: Your lovely short essay, "Audio Echo," springboards off a recording by Virginia Woolf. Without giving away the gist of the story, why did you choose to deal with that particular idea?

Robert: Early recordings of authors’ voices fascinate me. I was amazed to learn that Walt Whitman was the first person Edison recorded. And I’ve listened to the few recordings of James Joyce and other Modernists. It would be amazing to hear Emily Dickinson read even one of her poems. Poetry, of course, is a very aural art form. So hearing the voice of Virginia Woolf, who I studied in a PhD seminar, was the basis for my response as the actuality of her voice was placed in a relationship with the sound of her voice as I’d imagined it. Sound and scent are the strongest prompts for memories. Quite a prompt—but where to go in the writing? So I responded to a few statements from her radio talk on language. The shift to the visual text and her direct connection to the physical nature of her writers—knowing that she set the type for Hogarth Press—was not an illogical development for the narrative aspect of the piece as it developed by leaping (as Robert Bly calls it). But looking out the window while listening to her radio recording prompted the connection that launched the lyric moment of the piece.

Chila: I was impressed during the editing process when you mentioned that if we clarified a line, "The sentence and paragraph rhythm change, but it serves the overall piece ...." I rarely hear this type of concern over specific word choices, but with your comment you demonstrated a true understanding of what's needed to construct a successful lyric essay. How long have you been studying the lyric form and who has influenced you the most in this area?

Robert: The doorway through which I entered the lyric essay was through lyric poetry. The two share just about the only literary space in which the first person singular pronoun “I” is central to the speaker’s lyrical stance in relationship to the subject material. The two also share the risk of personal exposure, offering challenges, risks, exposure, and ultimately the freedom from artifice. By that I mean that in other genres—fiction, playwriting, persona poems—generally speaking, the pronoun “I” is either a mask or imagined character. It’s like saying that Shakespeare said “To be or not to be,” when in actually it is a character (Hamlet) in a play of the same name. But in lyrical poetry and the lyrical essay (and in all nonfiction) I stand in real time and speak, as it were. The poet Robert Creeley once wrote, “When ‘I’ speaks, I speak” (sic). Lyrical utterance makes me feel both anxious and exhilarated.

I came to the lyrical essay first through David Sedaris. His ability to lay himself open to the world in his humorous memoirs attracted me first as a reader and then as a writer. Poetry can be too somber, too intellectual, as if a poet believes that unless the poem is serious, the poet will never be taken seriously. Well, Billy Collins has dispelled that quite effectively. But humor is also play, freeing the imagination as it intuitively moves by its own instinct, which I envision metaphorically as like the way bees move when gathering pollen: it may look playful to us but to bees it is a serious activity. My longer nonfiction tends to be more playful, with tonal shifts for variation. For the brief nonfiction, I was significantly influenced by Polish-American Nobel Prize winner Czeslaw Milosz. His poems are not merely lyrical but personal, and often feel like memoirs with line breaks or prose excerpts from his personal journals. His Treatise on Poetry is a traditional verse essay, and his collection A Road-side Dog is filled with short pieces that inhabit the liminal space between a kind of meditative, philosophical prose poem that derives from a European tradition and a kind of brief lyrical essay that is becoming more prevalent in this country, one found in the company of prose poets and micro fictionists, often in the pages (screens) of online journals read by people on commuter trains or in coffee shops: quick reads for busy days. Reading Milosz’s brief lyric essays feels as if I am eavesdropping on his mind pondering an idea—where it begins, how it develops, transitions, arrives, contradicts, then moves on again—it’s like the idea itself becomes the hero in a narrative dressed in exquisite clothing, all recorded on a cellphone. That’s about as accurate and metaphorical an explanation I have of how I conceive of the brief lyric essay.

Chila: How often does your setting in northeastern Ohio influence your writing?

Robert: My book of short stories, And Your Bird Can Sing (Bottom Dog Press, 2014) is centered in the Midwest, with a number of stories set in Northeast Ohio, and some in Cleveland. Northeast Ohio has very changeable weather; as a result, it is a locale of changing moods, quick shifts. Along the north coast of the country, Ohio experiences “lake effect” which makes for long, late autumn warmed by Lake Erie’s water temperature, which drew settlers to the region who planted orchards and vineyards. It also made for cool Junes, particularly if the lake was frozen over during a long winter, so that the spring winds from the north “fan” northeast Ohio. For me, Northeast Ohio weather makes me aware of my relationship with landscape, with a site specific sense of interaction with place that shapes my attention to shift, drift, difference, to nuance and subtlety—traits that layer poems, stories, nonfictions. I suppose it is possible how this is reflected in the brevity of much of my writing: changing weather influencing my changing topics, genres, stances, tones.

Chila: Is there a special essay, long-form essay, or book you have in mind to write in the next year or two? If so, can you elaborate?

Robert: A pattern I’ve discerned about my writing shows that a first book in a genre tends to be corralling pieces written randomly into a collaged, unified body of work. This was the case with my book of short stories as well as with my first full-length book of poems, Hotel Utopia (New Rivers Press, 2011). I’m beginning to collate my existing nonfiction into a first draft of a collection, Electric Boulevard, with written nonfiction pieces starting to show recurring topics with their contrasts and variations, both in content as well as shape and length. This is an exciting point for me, because that awareness tends to generate new work that will add to the conversation that becomes a book.

Chila: You teach in the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts Program. What's the most rewarding part of your interaction with the students?

Robert: The NEOMFA [Northeast Ohio MFA in Creative Writing] is a unique program. It’s the only program in the country comprised of four universities [Youngstown State, Kent State, Cleveland State, and University of Akron] with a shared MFA faculty, located in Midwest “rust belt” geographic area that is about the size of New Hampshire or Vermont. It draws from a large and varied population of students who live in rural, suburban and urban areas that represent the Great Lakes culture, the northern tip of Appalachia, Industrial cities, and Midwest agricultural communities, all this with the Cuyahoga Valley National Park sort of in the center of it. What I find particularly rewarding is seeing how bringing diverse communities of writers associated with particular Ohio cities and universities into a larger, more composite community; bringing a diverse community of genre writers (nonfiction writers, playwrights, poets, prose poets, short story writers, novelists, hybridists) into the workshops and craft and theory courses form communities of writers unbound from the artificial limits of genre; and join myself with a community of multi-genre writer-teacher-scholars who are my colleagues and friends. Writing is at base always a solitary act, but it becomes enriched and rewarding when writers come together into communities based on shared vocation and interests.

Chila: Your lovely short essay, "Audio Echo," springboards off a recording by Virginia Woolf. Without giving away the gist of the story, why did you choose to deal with that particular idea?

Robert: Early recordings of authors’ voices fascinate me. I was amazed to learn that Walt Whitman was the first person Edison recorded. And I’ve listened to the few recordings of James Joyce and other Modernists. It would be amazing to hear Emily Dickinson read even one of her poems. Poetry, of course, is a very aural art form. So hearing the voice of Virginia Woolf, who I studied in a PhD seminar, was the basis for my response as the actuality of her voice was placed in a relationship with the sound of her voice as I’d imagined it. Sound and scent are the strongest prompts for memories. Quite a prompt—but where to go in the writing? So I responded to a few statements from her radio talk on language. The shift to the visual text and her direct connection to the physical nature of her writers—knowing that she set the type for Hogarth Press—was not an illogical development for the narrative aspect of the piece as it developed by leaping (as Robert Bly calls it). But looking out the window while listening to her radio recording prompted the connection that launched the lyric moment of the piece.

Chila: I was impressed during the editing process when you mentioned that if we clarified a line, "The sentence and paragraph rhythm change, but it serves the overall piece ...." I rarely hear this type of concern over specific word choices, but with your comment you demonstrated a true understanding of what's needed to construct a successful lyric essay. How long have you been studying the lyric form and who has influenced you the most in this area?

Robert: The doorway through which I entered the lyric essay was through lyric poetry. The two share just about the only literary space in which the first person singular pronoun “I” is central to the speaker’s lyrical stance in relationship to the subject material. The two also share the risk of personal exposure, offering challenges, risks, exposure, and ultimately the freedom from artifice. By that I mean that in other genres—fiction, playwriting, persona poems—generally speaking, the pronoun “I” is either a mask or imagined character. It’s like saying that Shakespeare said “To be or not to be,” when in actually it is a character (Hamlet) in a play of the same name. But in lyrical poetry and the lyrical essay (and in all nonfiction) I stand in real time and speak, as it were. The poet Robert Creeley once wrote, “When ‘I’ speaks, I speak” (sic). Lyrical utterance makes me feel both anxious and exhilarated.

I came to the lyrical essay first through David Sedaris. His ability to lay himself open to the world in his humorous memoirs attracted me first as a reader and then as a writer. Poetry can be too somber, too intellectual, as if a poet believes that unless the poem is serious, the poet will never be taken seriously. Well, Billy Collins has dispelled that quite effectively. But humor is also play, freeing the imagination as it intuitively moves by its own instinct, which I envision metaphorically as like the way bees move when gathering pollen: it may look playful to us but to bees it is a serious activity. My longer nonfiction tends to be more playful, with tonal shifts for variation. For the brief nonfiction, I was significantly influenced by Polish-American Nobel Prize winner Czeslaw Milosz. His poems are not merely lyrical but personal, and often feel like memoirs with line breaks or prose excerpts from his personal journals. His Treatise on Poetry is a traditional verse essay, and his collection A Road-side Dog is filled with short pieces that inhabit the liminal space between a kind of meditative, philosophical prose poem that derives from a European tradition and a kind of brief lyrical essay that is becoming more prevalent in this country, one found in the company of prose poets and micro fictionists, often in the pages (screens) of online journals read by people on commuter trains or in coffee shops: quick reads for busy days. Reading Milosz’s brief lyric essays feels as if I am eavesdropping on his mind pondering an idea—where it begins, how it develops, transitions, arrives, contradicts, then moves on again—it’s like the idea itself becomes the hero in a narrative dressed in exquisite clothing, all recorded on a cellphone. That’s about as accurate and metaphorical an explanation I have of how I conceive of the brief lyric essay.

Chila: How often does your setting in northeastern Ohio influence your writing?

Robert: My book of short stories, And Your Bird Can Sing (Bottom Dog Press, 2014) is centered in the Midwest, with a number of stories set in Northeast Ohio, and some in Cleveland. Northeast Ohio has very changeable weather; as a result, it is a locale of changing moods, quick shifts. Along the north coast of the country, Ohio experiences “lake effect” which makes for long, late autumn warmed by Lake Erie’s water temperature, which drew settlers to the region who planted orchards and vineyards. It also made for cool Junes, particularly if the lake was frozen over during a long winter, so that the spring winds from the north “fan” northeast Ohio. For me, Northeast Ohio weather makes me aware of my relationship with landscape, with a site specific sense of interaction with place that shapes my attention to shift, drift, difference, to nuance and subtlety—traits that layer poems, stories, nonfictions. I suppose it is possible how this is reflected in the brevity of much of my writing: changing weather influencing my changing topics, genres, stances, tones.

Chila: Is there a special essay, long-form essay, or book you have in mind to write in the next year or two? If so, can you elaborate?

Robert: A pattern I’ve discerned about my writing shows that a first book in a genre tends to be corralling pieces written randomly into a collaged, unified body of work. This was the case with my book of short stories as well as with my first full-length book of poems, Hotel Utopia (New Rivers Press, 2011). I’m beginning to collate my existing nonfiction into a first draft of a collection, Electric Boulevard, with written nonfiction pieces starting to show recurring topics with their contrasts and variations, both in content as well as shape and length. This is an exciting point for me, because that awareness tends to generate new work that will add to the conversation that becomes a book.

Chila: You teach in the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts Program. What's the most rewarding part of your interaction with the students?

Robert: The NEOMFA [Northeast Ohio MFA in Creative Writing] is a unique program. It’s the only program in the country comprised of four universities [Youngstown State, Kent State, Cleveland State, and University of Akron] with a shared MFA faculty, located in Midwest “rust belt” geographic area that is about the size of New Hampshire or Vermont. It draws from a large and varied population of students who live in rural, suburban and urban areas that represent the Great Lakes culture, the northern tip of Appalachia, Industrial cities, and Midwest agricultural communities, all this with the Cuyahoga Valley National Park sort of in the center of it. What I find particularly rewarding is seeing how bringing diverse communities of writers associated with particular Ohio cities and universities into a larger, more composite community; bringing a diverse community of genre writers (nonfiction writers, playwrights, poets, prose poets, short story writers, novelists, hybridists) into the workshops and craft and theory courses form communities of writers unbound from the artificial limits of genre; and join myself with a community of multi-genre writer-teacher-scholars who are my colleagues and friends. Writing is at base always a solitary act, but it becomes enriched and rewarding when writers come together into communities based on shared vocation and interests.

This was fascinating. So much thanks to Robert for his time, elaboration, and especially his essay. All good wishes to him in the days ahead. ~Chila

Robert Miltner has published Hotel Utopia (prose poetry from New Rivers Press) and And Your Bird Can Sing (short fiction from Bottom Dog Press). His nonfiction has appeared in Great Lakes Review, Diagram, AWP Writer, Buried Letter, KSU Research for Life, Mochila Review, and The Los Angeles Review. Miltner is Professor of English at Kent State University, teaches fiction and poetry in the NEOMFA, and edits The Raymond Carver Review. He is the recipient of an Individual Excellence in Poetry Award from the Ohio Arts Council.

Robert Miltner has published Hotel Utopia (prose poetry from New Rivers Press) and And Your Bird Can Sing (short fiction from Bottom Dog Press). His nonfiction has appeared in Great Lakes Review, Diagram, AWP Writer, Buried Letter, KSU Research for Life, Mochila Review, and The Los Angeles Review. Miltner is Professor of English at Kent State University, teaches fiction and poetry in the NEOMFA, and edits The Raymond Carver Review. He is the recipient of an Individual Excellence in Poetry Award from the Ohio Arts Council.